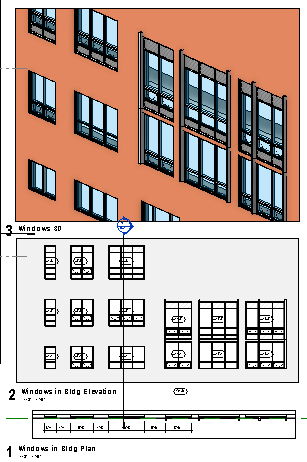

Architects assemble buildings from individual parts in Revit. Pre-set elements are part of templates and libraries for easy access. Any building starts from a kit of parts, just like the furniture from IKEA. A ready library of walls, floors, roofs, windows, doors, stairs, components, annotations, and formats can be customized to whatever you want for the design and documentation of architecture in the Revit Building Information Model environment. You can set it up as you please.

Best Practice

Is there a best way to approach to creating a uniform set of building blocks in Revit? Standards sometimes exist for standards’ sake and are not worth having unless they make things better. A good Revit standard keeps work clean and understandable, with fewer unnecessary steps or distracting choices; no need to “reinvent the wheel” every time. On the other hand, over-defined standards can become overwhelming, reducing speed and flexibility. The value of setting elements up before hand goes away if the Revit user is tempted to abandon the system and make what they need ad-hoc.Building the Library from Generic to Realistic

A kit of parts that works in Revit starts with generic components and extends to the more complex. No need to force detailed decisions early. Provide a basic spectrum of choices systematically named so the designer can find them. Show only to the level of detail that is needed to communicate clearly, which is no different that in the days of hand drafting. Just because we can show high level of detail in Revit doesn't mean we should. Don’t weigh the process down.

Look it Up

Look it Up

One of the most important aspects of a good library is to clearly codify the choices. A graduated series of standard components can be given short, logical, findable names. Keep the library small, containing just the parts that serve as “seeds” for duplicating to similar types parametricly. Human memory is limited, but we can always look it up, or make it as we need it according to a system. Standards should extend to the text, tagging and formatting of the model in all phases, from schematic through construction documents. Good standards streamline and help us visualize and communicate the work, The same model serves as the basis for clear diagrams and stunning presentations as well as highly technical documentation, with format styles already built in. In Revit, it is best to set it all up right from the start, with an effective kit of parts.