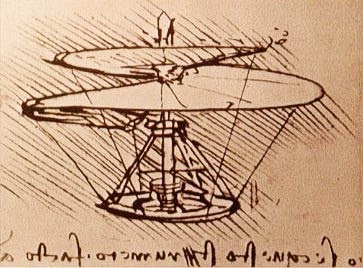

Architecture is broad in conception, but also intensely detailed. Two distinct forms of thinking are needed to get a design off the ground and a building into the ground. To resolve a design, the architect must branch out and explore, but also refine and nail down. Architects have a long tradition of how this process works: loose sketching of options, expressing and presenting proposals for debate, for decisions. Finally, design complete, there is a hand-off, and the process of committing to hard lines and exact descriptions begin. Narrowing down is relentless, so that the many interconnected details can be addressed. Proceed one step at a time, and, above all NO CHANGES to the design. This split promotes two cultures in any practice: the dreamers and the realists, each working in a separate room.

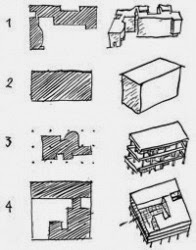

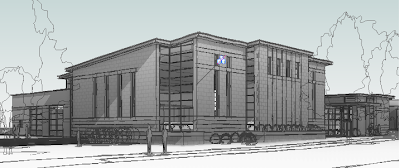

Enter the Building Information Model. Architects compose and link a network of objects to describe the design, giving the building coherent form, proportion,enclosure, structure, functions, and so on. The schematic design serves as the overarching outline of placeholders for a large amount of detailed information that will eventually be resolved.

| Schematic Design |

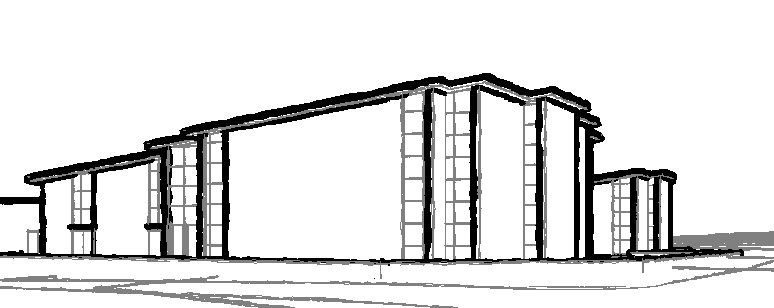

Peter Cholakis, in his Building Information Management blog describes it: "Some information is more appropriately located in the ‘geometrical’ part of the BIM object while other information is more suited to the ‘properties’ part, such as the specification. The specification is part of the project BIM, and objects live in the specification. In traditional documentation we would ‘say it once, and in the right place’, however with BIM, we want to ‘author it once, and in the right place, to be able to report it many times’. ...Take the analogy of a BIM object representing a simple cavity wall. The object will tell us the width of the brickwork and height of the wall. However at a certain point in the project cycle it is the written word that is needed to take us to a deeper level of information. It is within a textual context that we describe the length, height and depth of the brick. It is words that are used to describe the mortar joint and wall ties."

| Construction Documents |

Elements of the design are necessarily generic and simplified to start, giving power to organize the project. Elements are stripped down to their basic form as placeholders for extensive, interconnected detail to come. This is important in many fields. A satellite engineer from Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab I know uses placeholders, “At the beginning of a project, the exact nature of the content may not matter, or even exist yet. Or maybe having actual content would be too distracting from the problem at hand.”

Graphic and web designers have been know to use lorem ipsum, and even placekittens to hold the place of eventual text and images to help bring focus to the task of structuring the page or site.

| Lorem Ipsum placeholder text |

That is my vision for BIM in the workplace. What is your experience? Does BIM actually foster flexibility in design, increased collaboration, more integrated detail, or is the verdict still out? Looking forward to seeing a dialogue in "Comments".