|

| LeCorbusier's Modulor |

The Beginning

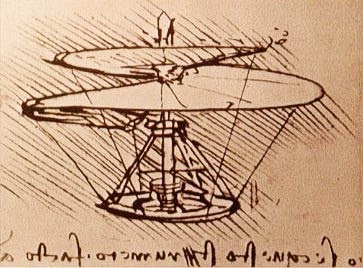

When I studied architecture in the late 1970’s at Cornell, I learned from the work of the modern masters: LeCorbusier, Mies, Wright, Aalto, Kahn, and some newer folks: Meyer, Stirling, Rossi, and others. Thanks to professors Colin Rowe and Mathias Ungers, we were also pointed back to the great precedents before the modern era, and pointed forward to the larger world around us. Design started with criteria for the program and the context. A parti, the big idea, was diagrammed and tested. Architectural elements, including walls, floors, roofs, and openings, built on the parti. These were the elements of architecture , with the designer sketching, drafting, and rendering, and, at times, building a physical model to work out the idea.

The CAD Era

Shortly after I went into practice in the 1980's, the digital age brought a new, helpful, but demanding tool into architecture: Enter Computer Aided Design and Drafting (but with special emphasis on “drafting”). Not purpose built for Architects, CAD had its beginnings in Aerospace. Any discipline could use it for any kind of delineation (I remember my surprise when I saw "Ångström" as one of the choices for setting the units, not just feet or meters). A new vocabulary came to dominate our work: Point, Line, Layer, Xref. The tool brought incredible accuracy, but its narrow focus often distracted from forming ideas and buildings.CAD came to dominate how we developed designs and produced construction documents, taking the place of the team of hand drafters of past eras. Most simply used it for more efficient 2D drafting. AutoCAD did offer awkward 3D tools within its software packages, but these would go largely untapped. Outside applications crept in, like Sketchup and 3DMax, out of sheer necessity to see the building more fully. Adding and scheduling elements of the building remained a "one item at a time" process, with some assistance from the copy command and spreadsheet software. The computer had automated and integrated the working process in many fields in the 1980's and '90's, but not in architecture.

Back to the Beginning

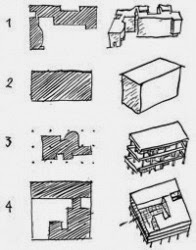

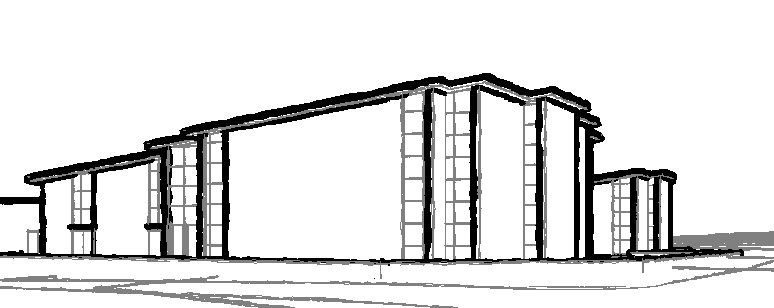

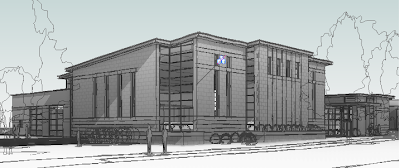

By 2000, advances in computing started to offer a practical road back to the original focus of architectural design, and leave traditional drafting behind. Architects could begin to work directly in an integrated environment of the virtual building model that completely linked information, and creating a wide variety of 2D and 3D views automatically. When I became aware of Revit as one of these new accessible BIM packages 10 years ago, I jumped in. Away with machine drafting to trace out buildings in in a complicated sequence of glowing vectors and color coded layers. I missed architecture.Since then, I have been immersed in the virtual building information model. I am back to the conceptual basic building blocks of wall, column, floor, and roof. I now mold and describe forms, space, and functions as I learned in school. Endless cross references from drawing to drawing update themselves as details shift and change. I am writing this blog, Revit Reflections, to explore ways Revit has energized my work as an Architect, and, in many ways, brought me back to my roots.

%2B-%2BCopy%2Bof%2BLevel%2B1.jpg)